I couldn’t get Worsham out of my head. It felt like he’d burrowed into my brain through that slimy handclasp. I writhed in discomfort every time I recalled the encounter, ashamed I hadn’t handled it more forcefully. I dealt with my own sense of impotence the way I always did: I went digging again.

I couldn’t get Worsham out of my head. It felt like he’d burrowed into my brain through that slimy handclasp. I writhed in discomfort every time I recalled the encounter, ashamed I hadn’t handled it more forcefully. I dealt with my own sense of impotence the way I always did: I went digging again.

This time I centered on Worsham’s past. I’d been so busy up until now, just keeping pace with his outrageous lies and constant attacks, I hadn’t had time to look backward. But meeting him, even aside from the whole sleazy menacing hand-licking thing, there was just something about him, in person, that felt… off. I told myself I could chalk it up to simple repulsion on a chemical level, but whatever it was, I seemed to feel it viscerally, as if even his DNA wasn’t on the up and up. Who was this guy? Where did he come from and what made him the way he was?

You’d think, in that day and age, no one would be able to hide from the media. And yet, when it came to Worsham, the paper trail was strangely opaque, convoluted, contradictory, and maddeningly incomplete.

I took it as a personal challenge, and a way to redeem myself.

No one seemed to know anything for sure; everyone had heard a version of his life, including people who worked for him or with him. One of the most persistent stories was that he was from a small town in Nebraska. Western Nebraska. Or was it southern? Or north central? The name of the town varied from telling to telling, too, even though in every one of the surprisingly few biographical articles, the person giving the information spoke as if he or she was a close personal friend from childhood.

Okay, I thought. I picked a direction and started calling court houses in the western part of the state, county by county. I could get like that when I got engaged, determined and systematic. Okay, obsessive. I didn’t care if I had to go through every county in Nebraska.

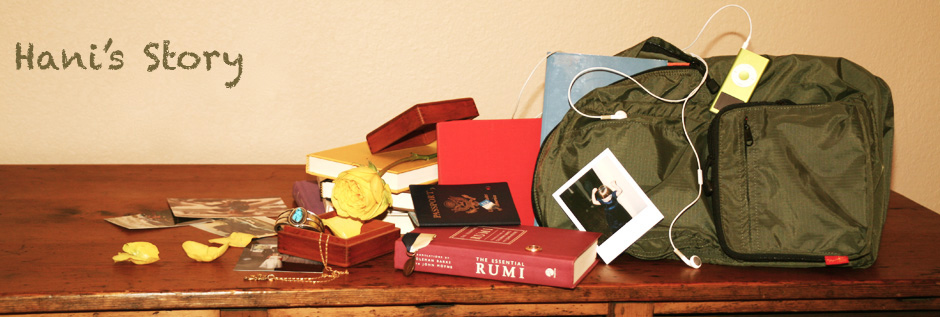

This I did over the course of a week or so. I didn’t often have large blocks of uninterrupted time. Bob’s doctors had sent us on to another specialist, in the hopes that a new experimental trial might buy him some time. It broke my heart in a way. Bob was so weak by then, just slogging through yet another hospital took so much out of him. He utterly hated wheelchairs, hated me having to push him, but that week was a bad one, and there I was, wrangling the chair down new corridors, new hospital buildings, Bob loyally holding my laptop and bag on his lap.

So, I’d worked my way through four counties so far. It wasn’t that easy. Those little rural communities aren’t really professionally staffed, and the person who can help you is often busy with other business, or not even there the day you call – or maybe for days on end. I’d just gotten my fourth negative from a really nice old gal who helpfully went and searched through the birth certificates herself. Nope. Not a sign of a Lester Worsham ever born there.

Bob had a bad night, that night. We had to rush him back to the emergency room, where they diagnosed a reaction to his latest med, the one he’d begged for, the one he hoped would turn things around. By the time we got home, we both collapsed, and slept until after lunch. I missed my own deadline, and so I might have missed the story, too. But that evening I got a call from a colleague at NOW whose job included monitoring the media. Worsham had just gone on air that day to share some shocking news. A gas leak had caused a massive explosion in his hometown of Cullen, Rooker County, Nebraska. The county courthouse was completely destroyed.

All county records were, of course, destroyed.

Oh, and 6 people were killed in the explosion.

Such a tragedy.

Cullen County had been next on my list to call. If I hadn’t met him, hadn’t actually gotten his measure, I might have been able to give Worsham the benefit of the doubt. Now, this guy simply scared the living daylights out of me. What the hell had I gotten myself into?